History is a clock that people use to tell their political and cultural time of day. ~ John Henrik Clarke.

It has now been a quarter of a century since South Africa emerged, bright-eyed and hopeful, from the destructive past of Apartheid. With the passing of time, giants of the South African liberation movement are dying, and they are taking with them their memories. We are steadily losing access to the first-hand accounts of those who fought for our hard-won freedom. Forgetting poses a threat to the survival of our democracy. It was George Santayana who said: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”.

Nombulelo Shange, a sociology lecturer at the University of the Free State and a millennial, says films about pre and post-Apartheid help her remember the past.

“As much as I am in a profession where I am forced to engage with literature [on the subject], something about the visual representation and the sounds and the characters sounds, and emotions help me to never forget,” she says.

Much has been done to preserve the country’s history through literature, music and museums. However, none have been as successful as the visual medium of film in telling the story of South Africa’s struggle to transmute itself into a democratic society to a wider audience.

The medium is more accessible than books, which require a level of literacy and an inordinate amount of time to consume. Unlike music, more complex information can be packaged into a film. Watching a film does not require travel to access places like Robben Island, or the Apartheid Museum.

Before the dawn of democracy, when the idea of a free and just society was little more than just a dream, movies, films and television programmes were made internationally about the plight of South Africans living under the National Party.

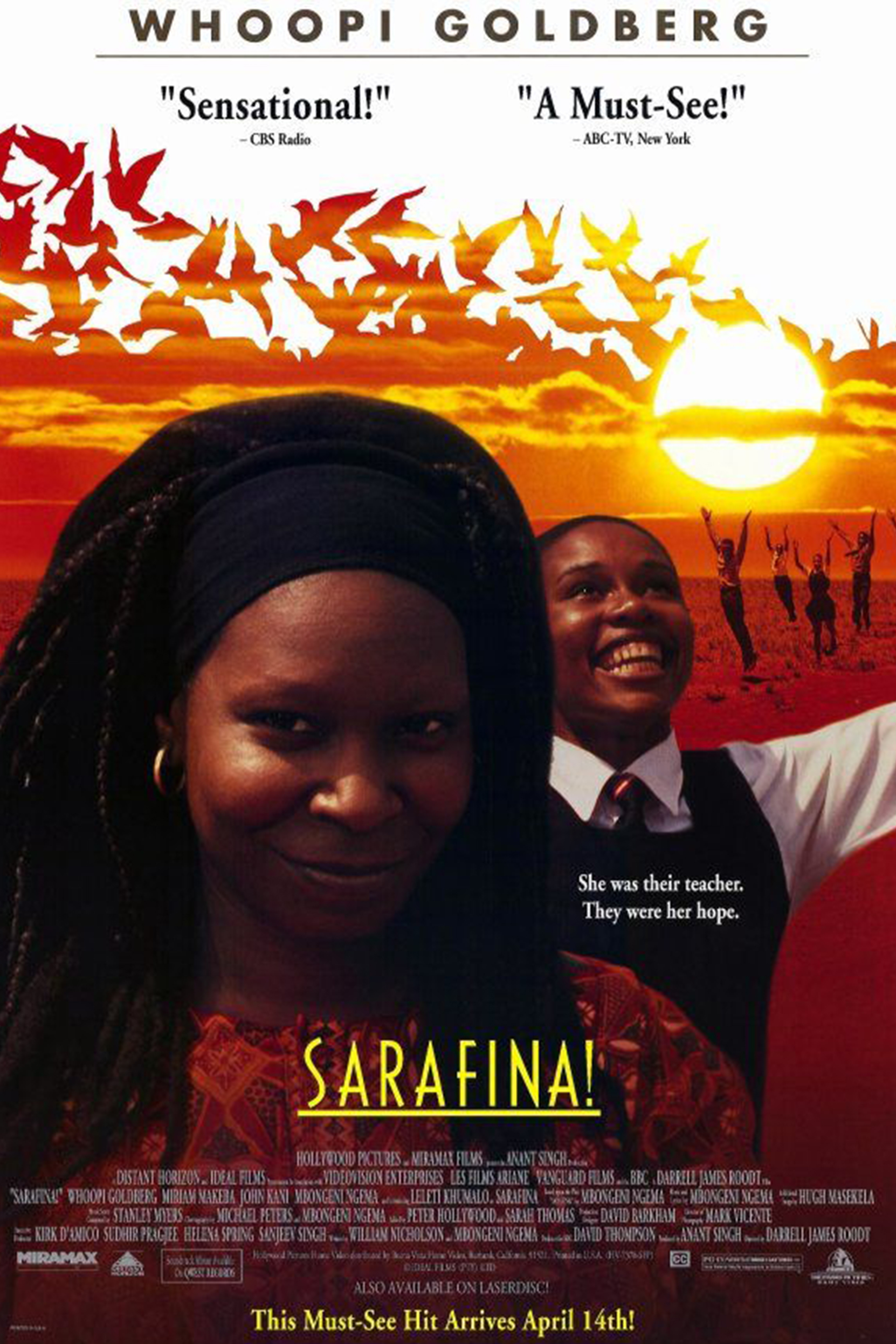

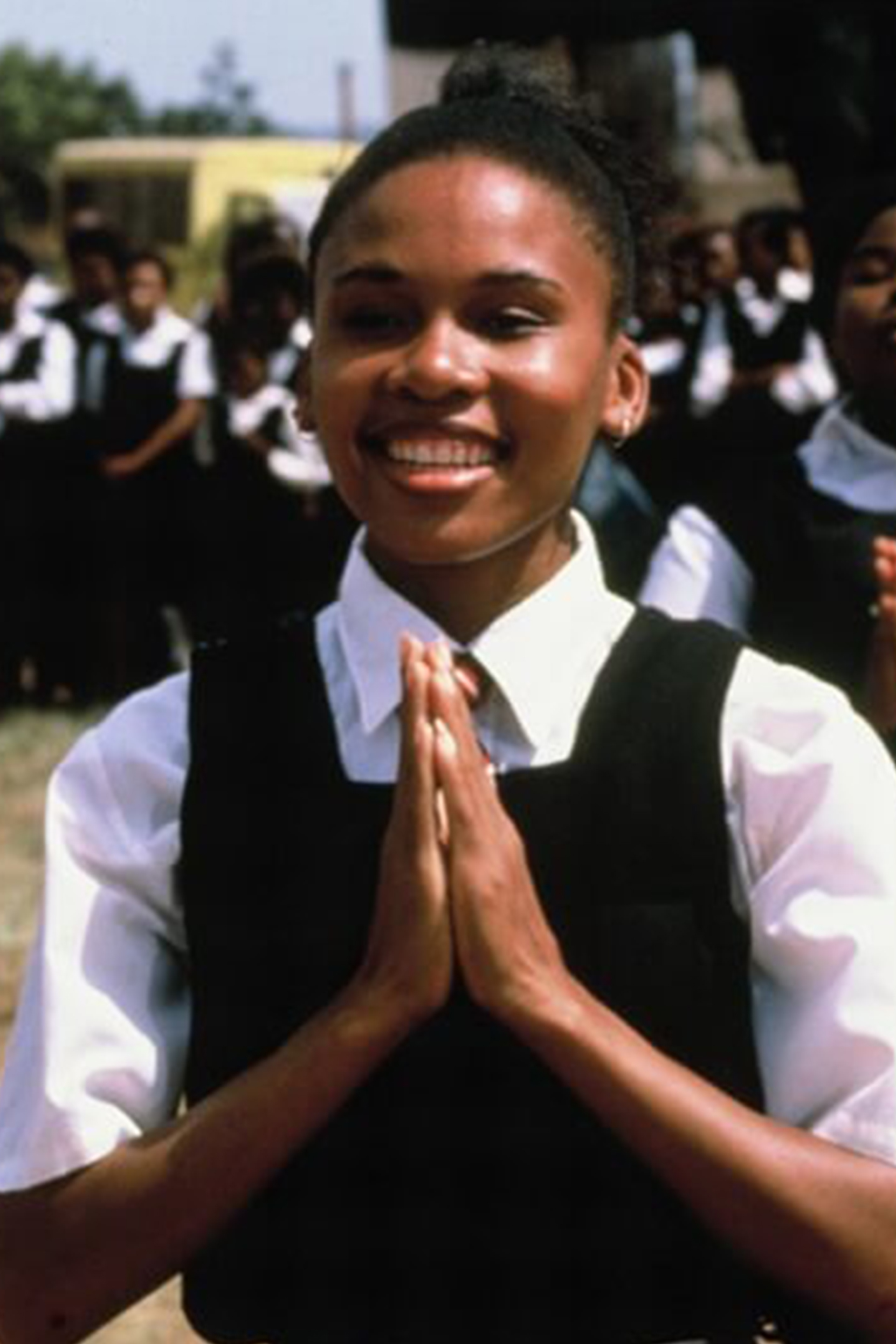

Films such as Mandela, a 1987 television drama film, which deals with the life of the late Nelson Mandela, and A World Apart, a 1988 film which tells the story of white struggle icons, Ruth First and Joe Slovo helped highlight the courage, fortitude and commitment of South Africans who rose to the challenge of fighting for change. Amongst films such as these, one that stands out for many is Sarafina! A movie documenting the grisly reality of life under National Party domination. The film, released in 1992, tells the story of students involved in the Soweto Uprising in 1976. Told through the eyes of a young girl, Sarafina, the movie shows the determination and courage of the country’s youth to fight against the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in schools across the country. The film is raw and uncomfortable to watch and does not shy away from showing the harsh, inconvenient truth about what was done to South Africans under the Apartheid regime.

Shange says Sarafina! has had the most impact in her life. “It deals with young people. I feel their struggle more; I feel their pain more, because I am a young person myself. I feel like I can relate more to those kinds of issues”. That unlike other movies such as Cry, Freedom, Sarafina! does not have a “white saviour” makes the movie more relatable for her.

“The movie showed that Black students that came from nothing were able to challenge the system. Often these movies, in as much as they [do] remind us of the past, always glorify white people. We saw it with Invictus, and the movie that focussed on Nelson Mandela and his jailor,” says Shange.

Growing up I don’t recall much conversation around the topic of Apartheid. Although my parents grew up in the Transkei, a separate Bantustan which gained independence in 1976, not much was said in our household about that time. Most of the information about the time filtered through my consciousness from white history teachers, most of whom tended to avoid the uncomfortable topics and focused more on dry recitations of dates and events.

My first exposure to the realities on Apartheid came from watching an old copy of Cry Freedom.

The film was released in 1987 and deals with the relationship between liberal journalist, Donald Woods and eminent struggle hero Steve Biko. That old tape was my first introduction to the man and his story. In the movie, Biko, who was known as the Father of Back Consciousness, is revealed to be a great mind committed to the emancipation of black South Africans. Set during Biko’s banishment to King William’s Town, the film showed the reality of Black people who were forced to live in appalling conditions due to laws imposed by the government.

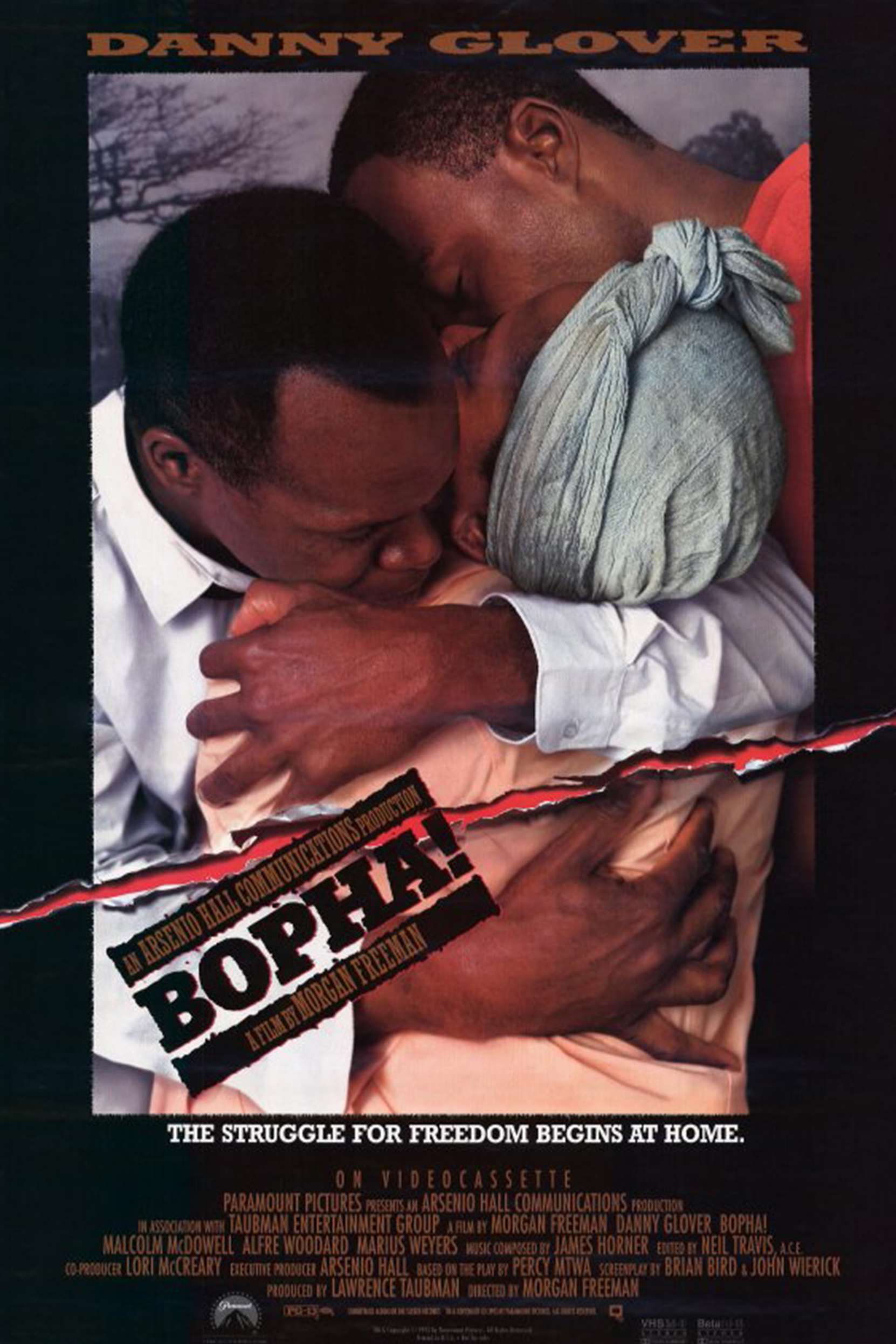

Unlike other icons of the struggle against Apartheid, Biko is one of the lesser known icons. The mainstream narrative about his life focuses mainly on his death at the hands of the Apartheid government in 1977. Cry Freedom brought into sharp relief Steve Biko’s black consciousness ideals, his love for Africans and his sharp intellect. Francisco Pedro, a white South African man in his early thirties, says he was introduced to the realities of Africans during apartheid story through film. The movie Bopha! was his first glimpse into the reality faced by his fellow South Africans. “It put in focus the plight of other people. You don’t really know how bad things were. It’s difficult to fathom the life of a person living in a one room shack,” he explains. Bopha! he says, also showed him the sheer scale of the brutality meted against people who fought for the liberation of South Africa.

“At the end of the movie, they also had a list of all the people who allegedly died in prison,” he says.

Films also have the ability to educate the older generation who grew up during the struggle. Kathy Pedro, Francisco’s mother says the National Party made sure that white South Africans were shielded from the realities of Black people during apartheid by rampant censorship and the banning of “subversive” materials.

“We as white people who grew up in that era were not made aware of what was going on,” she explains. Kathy says a viewing of the Mandela: Son of Africa, Father of the Nation documentary released in 1996 opened her eyes to what was happening beyond the gates of her manicured lawn.

“My aha moment was when I realised everything that Madiba had gone through,” she says.

Films not only serve to educate and keep the memories of those who fought hard for the liberation of South African alive, can also tell a different side to predominant narratives, and provide alternative views.

Following the passing of Winnie Madikizela- Mandela in 2018 many people, particularly young women, flocked to watch the documentary Winnie. The film tells the story of one of the most powerful women during South Africa’s history. Following the imprisonment of her husband Nelson Mandela, Madikizela- Mandela was forced to pick up the baton and continue pursuing the liberation of her people. Instead of focusing on her role as merely the wife of the great Nelson Mandela, the film portrays her as a fearless leader who risked her life, the wellbeing of her children and everything she had to advance the aims of the African National Congress (ANC). This was during a time when most of leaders had fled to exile or were languishing in prison. Winnie uncovered some of the betrayals she experienced during and after the struggle and her fight against attempts to delegitimise, silence her, and vandalise her legacy.

Winnie humanises Madikizela-Mandela. It is a stark change from the dominant narrative which often portrays her as a potential murderer, kidnapper and unfaithful companion, thereby erasing her enormous sacrifice in ensuring the success of the liberation struggle. It also reveals the faces of those who worked hard to erase her legacy from the mainstream using underhanded tactics, complicating the status quo and starting a debate on the fairness of how she has been represented. Considering recent struggles faced by young people, particularly in the Fees Must Fall movement, Shange says now, more than ever, South Africa needs more home-grown movies about struggle icons, to inspire young people. More importantly, the stories of lesser known icons need to be explored, she explains.

“I think it’s important now more than ever to make struggle movies [ that move] away from the mainstream narratives of Madiba this and Madiba that. I think it needs to be more about community stories and things that happened to ordinary South Africans who have never been recognised in history books”, she says.

Local film makers have started making these kinds of films. Kalushi, released in 2017, tells the story of a young freedom fighter, Solomon Mahlangu. The film was well received by South Africans suffering from fatigue induced by rehashed narratives about the same heroes. Shange says our generation, the generation born before the dawn of democracy, grew up at a time when the wounds of apartheid were still fresh, and the memories were still raw. Today though, things have changed somewhat, she says.

“I notice with my students at times that they are so disconnected from the reality, they understand the past in a way that is very superficial, and they don’t know their history and I find that to be very troubling.”

Instead of forgetting about the past as some in our country would like to, it is perhaps important to recall the past and ensure that nothing like it ever happens again. As a medium of storytelling film is perhaps the best way to ensure that the legacy for the country’s liberation icons is kept alive. As imminent scholar Octavia Utley says: “The … tradition of storytelling makes it possible for a culture to pass knowledge, history, and experiences from one generation to the next”.

thebar. Magazine

thebar. is an online magazine, concerned (read: obsessed)

with the local and international film industries.

Our purpose is to elevate these industries and their leaders

by showcasing high quality, breakthrough content which

elicits a strong response from those working inside

the industry and outside it.